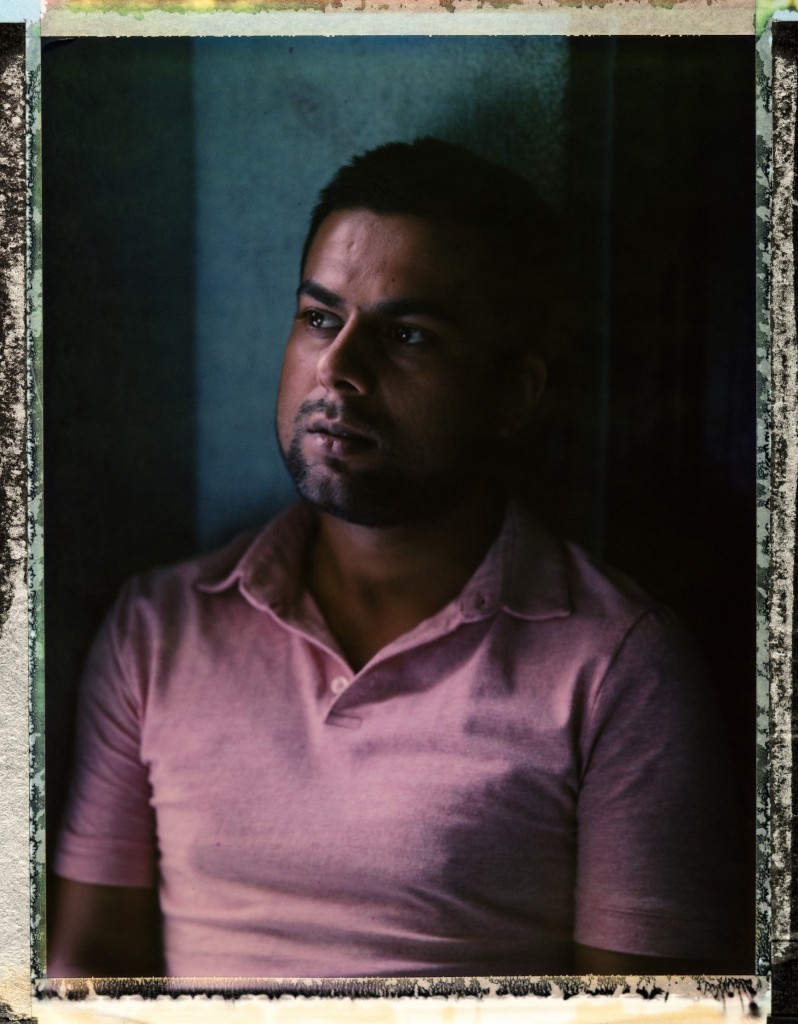

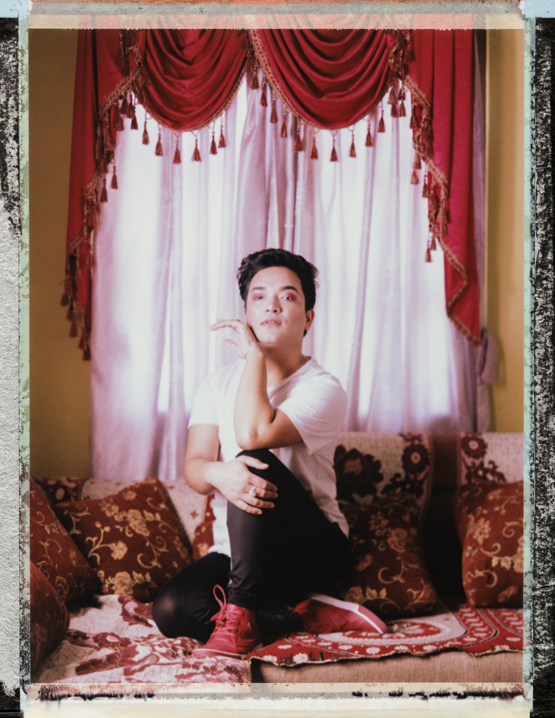

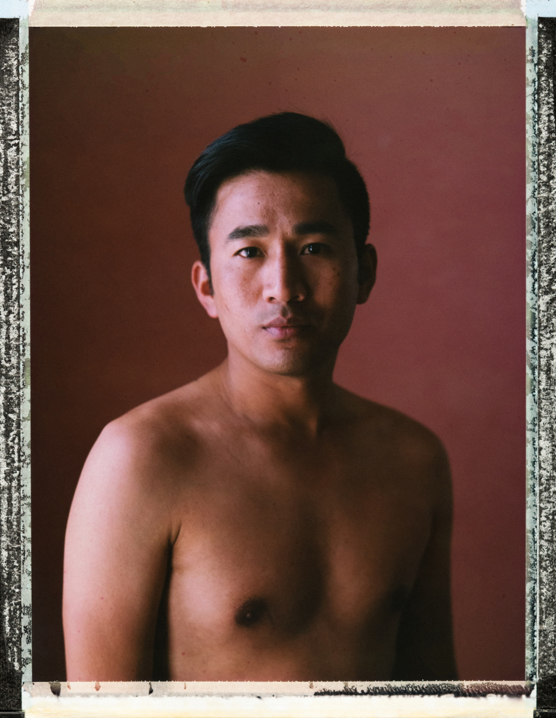

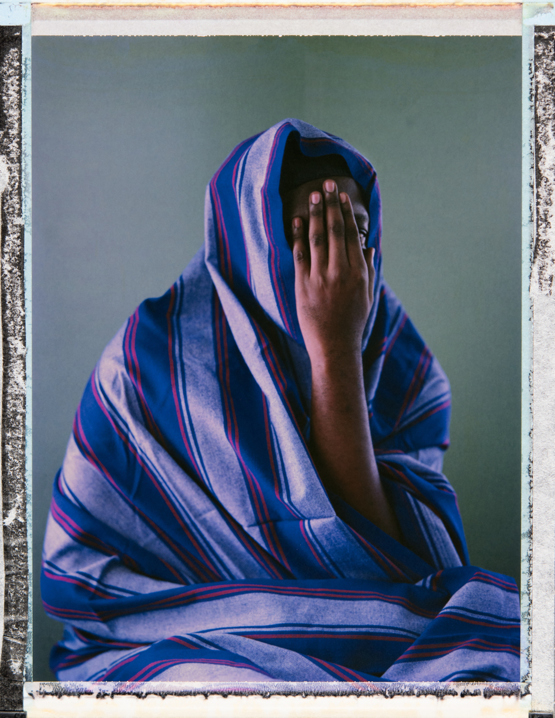

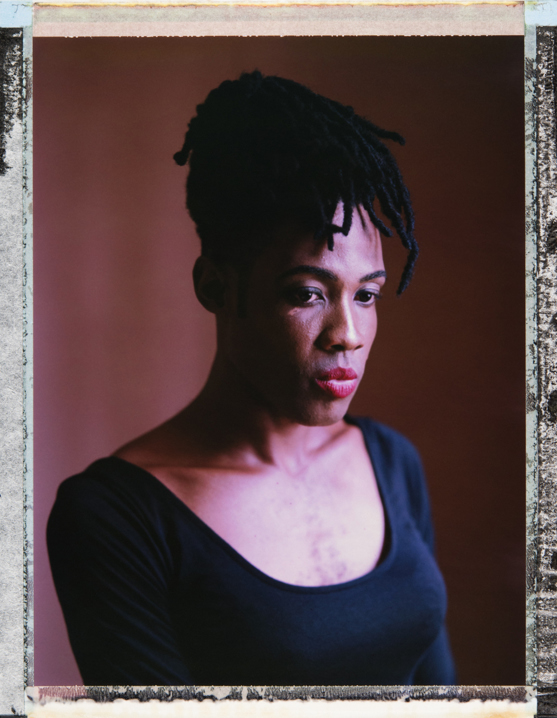

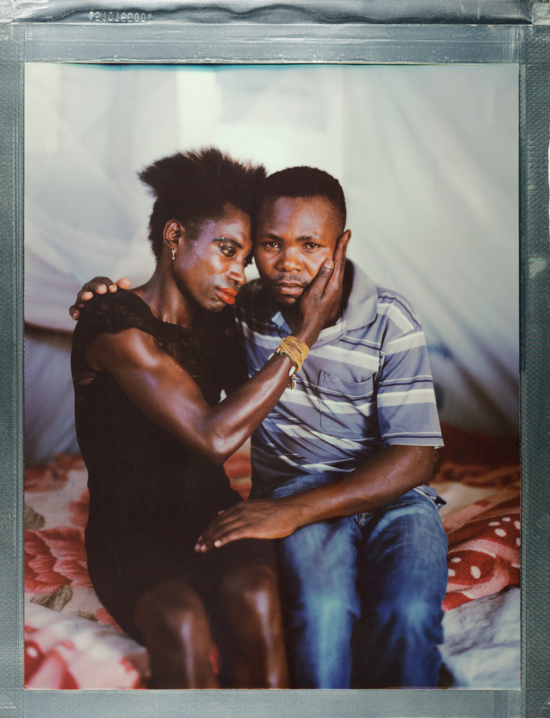

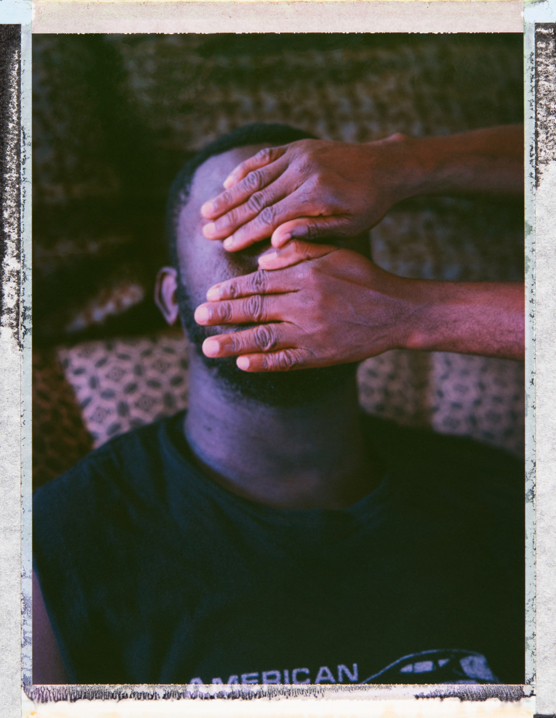

Joel/

Uganda

“But my older brother wouldn’t accept it, and one evening he called some friends and they dragged me out of the house on to the street, hit me and souted to the entire village ‘Joel is gay’.”

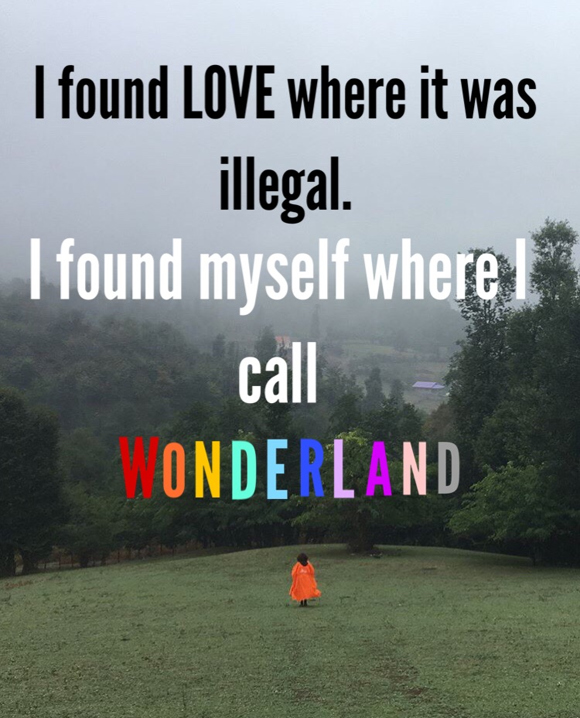

READ THE STORYDespite gains made in many parts of the world, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people are, in some regions, increasingly persecuted and denied basic human rights. Because bigotry thrives where we are silenced by fear, we've created this space for people to share stories of discrimination and survival. Read these stories, share them, and contribute your own. Let the world know that we will not be silent.

“But my older brother wouldn’t accept it, and one evening he called some friends and they dragged me out of the house on to the street, hit me and souted to the entire village ‘Joel is gay’.”

READ THE STORY

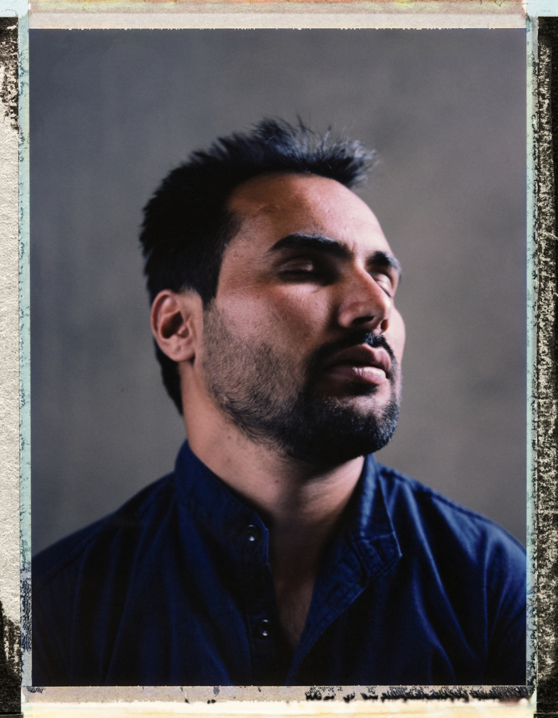

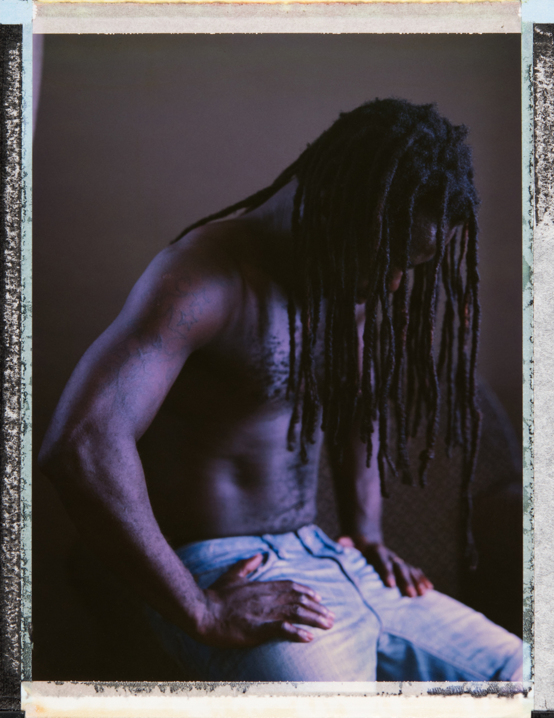

“I put on a mask (Jethro), I acted like I didn’t care for anyone or anything. The mask that allows me to hide my identity, the mask that makes my parents think that I’ve changed. The mask that got me my freedom”.

READ THE STORY

“At the very first day I wore a ladies clothes that time felt that magician sword touch my head and I became a lady… I was so happy that my dream came true.”

READ THE STORY

“I am a gay rights activist and fighting with society for claiming the equal rights where all LGBTIQ can live with equal rights and dignity.”

READ THE STORY

“I left my country to find a peace but i was not able to ..my life is more wrost”.

READ THE STORY

“, I was forbidden to tell anyone I was gay, they threatened me to let me out of the family, they asked me to go to a psychologist to ‘fix me'”

READ THE STORY

“I used to live a pretentious life with double standard out of the fear within me and of course the social prejudices that exists not only here but everywhere.“

READ THE STORY

“I don’t want to tell them because if i want them to accept me like i am, i should also accept them for who they are (people who can never understand).”

READ THE STORY

“I was force to start life on my own at the age of 16 after I was attack and almost killed by members of my family”

READ THE STORY

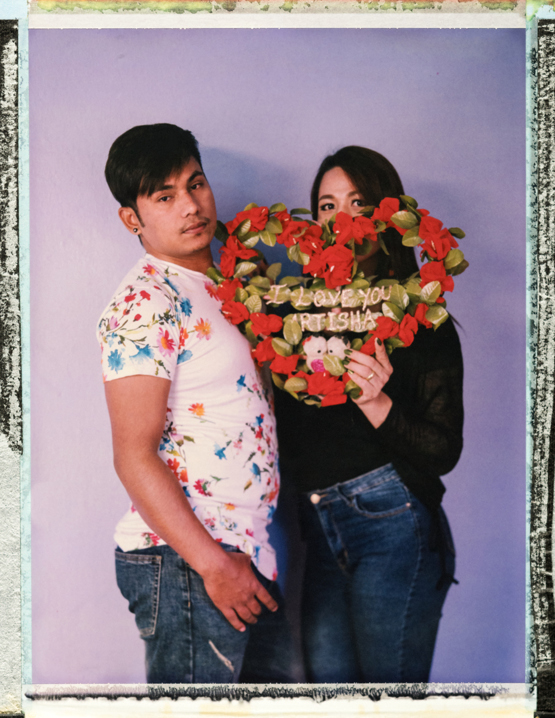

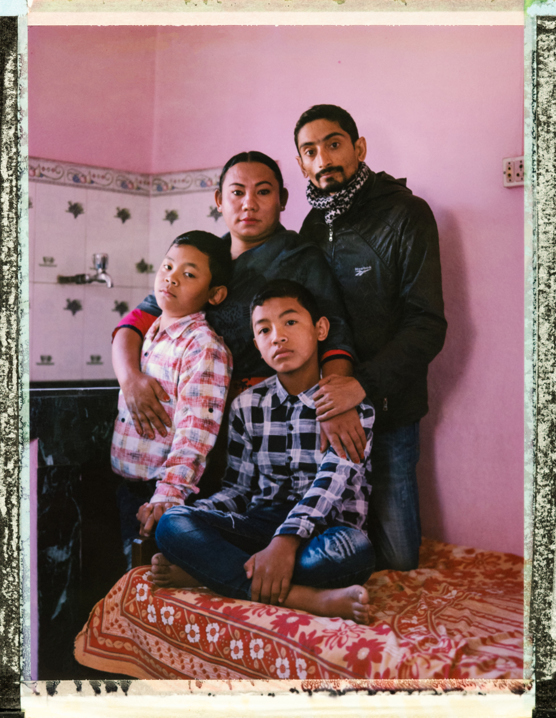

“Same sex marriage has not been legalized in Nepal. Don’t we have the right to live like straight couples and get the legal recognition? Aren’t we equal like other citizens of the country?”

READ THE STORY

“I was attracted to boys since I was eight years old. I always thought that I was a girl. I preferred girl’s roles when playing make-belief games.”

READ THE STORY

“This is not me, I thought, So I made up my mind to come clean. First I came out to my family. Their reaction wasn’t good neither was it as bad as I had imagined.”

READ THE STORY

“I was once homeless. Now I am prestigiously crowned Miss Pink Nepal 2018 It’s a prestigious stage for transgender women in Nepal. Its a great thing and a great achievement of my life.”

READ THE STORY

“I spent nights crying tears on cheeks tears on my pillow I couldn’t cry out loud because if someone hear me they would think I am a monster and pervert I felt so weak and alone I hated myself and I tried to change but one day I stood up and said to myself what if this would be ur last day in life would care about what others say would u care about all the people who are trying to put u down ?”

READ THE STORY

“I participate this program finally I am select in top 5 finalist and I won a title Mr. Gay Handsome congeniality. Then I face interview on national fm radio by this interview my other straight friends know about me. I feel lucky they message me and call me to encourage for my work.”

READ THE STORY

“WE Grew Up In THE 80S, IN A Time When Things WERE CHANGING, BUT Not ENOUGH THAT WE Could RISK ANYONE FINDING Out Our FRIENDSHIP WAS ACTUALLY A RELATIONSHIP.”

READ THE STORY

“Right through high school I have always admired and loved being with men. My family did not accept my sexuality because of my mixed culture and religion. I was told if I choose to be who I am, I will be disowned and in order not to disgrace them.”

READ THE STORY

“I am openly gay on facebook. This meant that most of the love messages turned into hate ones; moreover, some people wrote to me how they wished that i would get cancer again”

READ THE STORY

“As long as I remember,i was 5 years old when i was bullied for the first time. Hindi derogatory words like Hijra,Chakka etc. Were thrown to me and these WORDs really had an IMPact on my childhood.”

READ THE STORY

In many places the ‘I’ is kept separate from LGBTI. But within the I—the same way man and women can have different sexual orientation and gender identity—its the same with an Intersex person.

READ THE STORY

“I’m Kiria. I’m 24 years old. I admitted to my sexual orientation naturally and discovered it at the age of 10.”

READ THE STORY

“I was gay from day one. I discovered my sexuality and sexual preference very early in life.”

READ THE STORY

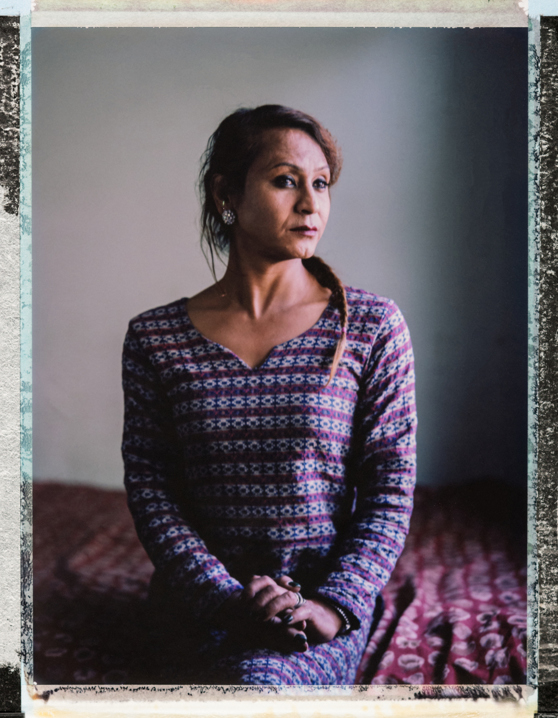

“My sons have accepted me as their mother and Shankar as their father. We live as husband and wife, like any other couple. We are happy. It has been eleven years.”

READ THE STORY

“I realised that I was a transgender when I was 13 years old. I have not studied a lot. And I studied up to third grade in my village. At the age of 13 I ran and came to Kathmandu.”

READ THE STORY

“I found out my true orientation it wasn’t hard for me to accept myself, but when I told it to my sister she said: I wished you chose an easier life.”

READ THE STORY

“I lived my entire childhood listening to offensive words from my parents, friends, classmates, neighbours, etc. But I never got carried away by those words, because I did not ask to be born like this.”

READ THE STORY

“This is a message I pass to your friends: if you know your friend have a problem, don’t run from him. You two are like that. Stay with him. Give him hope. All of the world is not in Kakuma only. Every place where there’s LGBTI like us, help them.”

READ THE STORY

“I was taken to churches, special places, because they felt I was possessed. As I became more feminine, society started frowning at me. I was called all sorts of names, lynched, hooted at, and that made me felt really uncomfortable. At a point, I wanted to commit suicide.“

READ THE STORY

“i was praying and asking why i born gay, i hated think that i was gay, i didn’t wanna be gay”

READ THE STORY

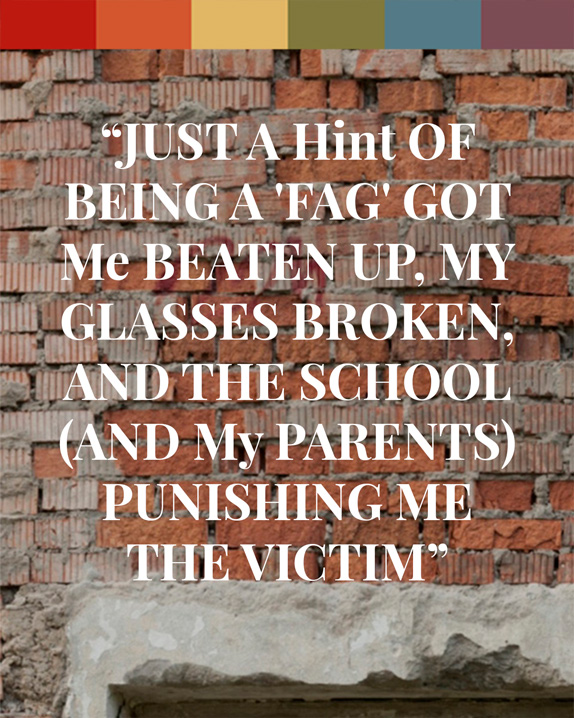

“WHEN I WAS BARELY 7 YEARS OLD AND SOMEONE CALLED ME GAY FOR THE TIME BECAUSE I SOUNDED LIKE A GIRL. IT WAS FROM THEN ONWARDS A FREQUENT QUESTION AND IT WAS ALWAYS IN THE BACK OF MY MIND, TRYING TO CHANGE MY BEHAVIOUR SO PEOPLE THOUGH I WAS STRAIGHT. IT NEVER WORKED TO MY FRUSTRATION.”

READ THE STORY

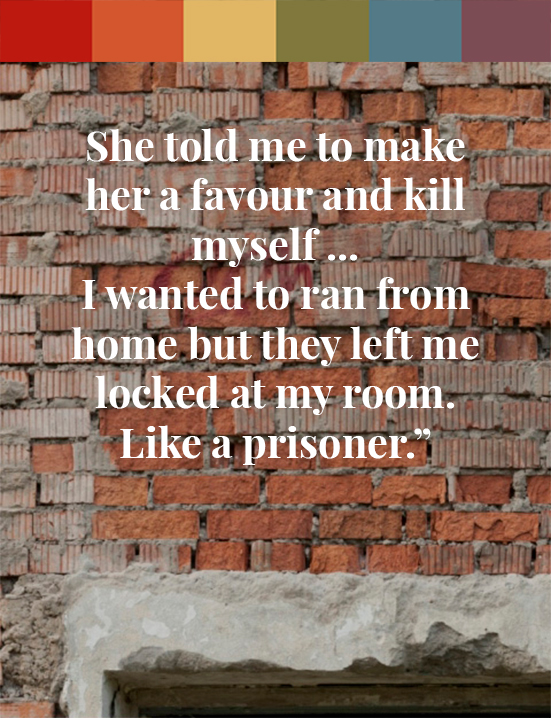

“Saturday, December 2nd. Mom I like girls And after that it all went cursing and yelling me to suicide. She (as a mom) doesnt deserve that. She told me to make her a favour and kill myself. I went familyless from that moment. She called my girlfriend and told her that she better stop calling … READ THE STORY

READ THE STORY

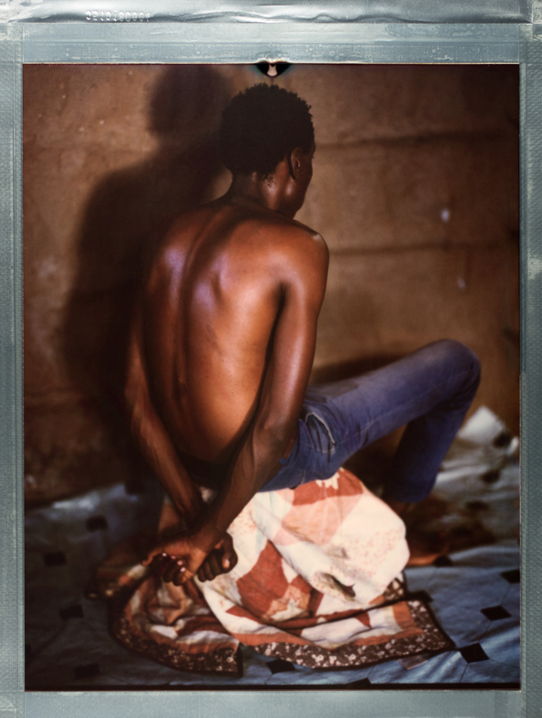

“They took me to the village, in a mud house, they locked me up, and called me a devil. That a devil’s supposed to be locked up. They left me there.”

READ THE STORY

“I’m 30 years old and my life is basically over i have no friends, i am being opressed by my family”

READ THE STORY

“People called me names ’cause I had little female tendencies and that mostly discouraged me and made me feel I was less of a human.”

READ THE STORY

“I came out when I was 25, in a country where I felt safe and to A family that might not understand, but supported me. I thought discrimination was far from me, but I was wrong.”

READ THE STORY

“After cOming out, my mom Dissed me. My sister threatened my life. My friends walked away. Was that not enough? Unfortunatelly no”

READ THE STORY

“I was trying hard ‘to pray the gay away,’ spending all my energies and resources for the religion, going on missionary work in other countries, but a storm was brewing within me”

READ THE STORY

“Growing up in a country where being gay is sin and abnormal was hard and sad I learn early in my life to be strong standing for my own right”

READ THE STORY

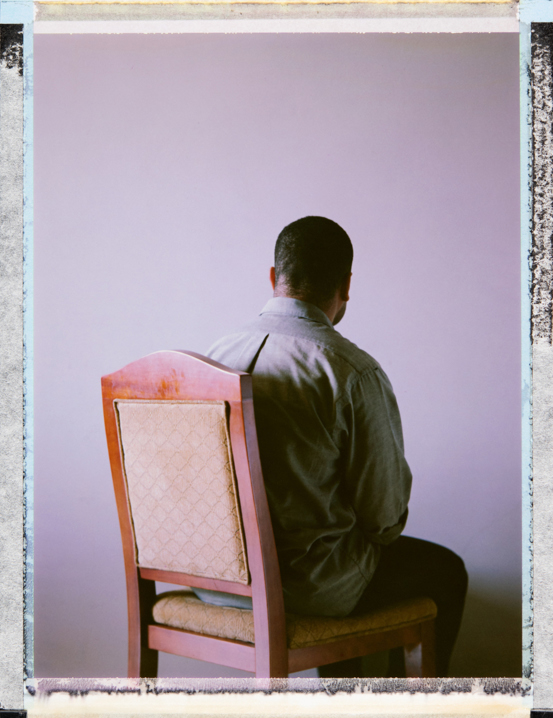

“I don’t want to write because I dont want to Remember, it makes me very angry. But most Importantly, I want to move forward”

READ THE STORY

“I stayed there with this man not being able to leave the house, not even to visit friends because he said I would go back to prostituting myself. I suffered physical violence, verbal and psychological abuse for one year.”

READ THE STORY

“Hi My nickname is Arash Randy. I was born in Iran and lived in Iran for 24 years. im now 29. After I was 24 years old, I escaped from Iran to Turkey and I applied for asylum. After spending 14 months in Turkey, I decided to move to Germany alone. Homosexuality is illegal in … READ THE STORY

READ THE STORY

“we had gone to the Clinic 7 hospital one day and met a group of Sudanese who shouted when they saw us and even brought tires and firewood saying they wanted to burn us. They ended up beating me and my husband. We were out of hope when the UN car came and took us to clinic 7.”

READ THE STORY

“Nine months down the lane we had a baby, our heaven on earth. He’s our everything, our life and our future. Sometimes when we are settling our differences and he walks in on us, in the heat of everything, he smiles and then takes all the tension away. I could say he’s the pillar of this relationship.”

READ THE STORY

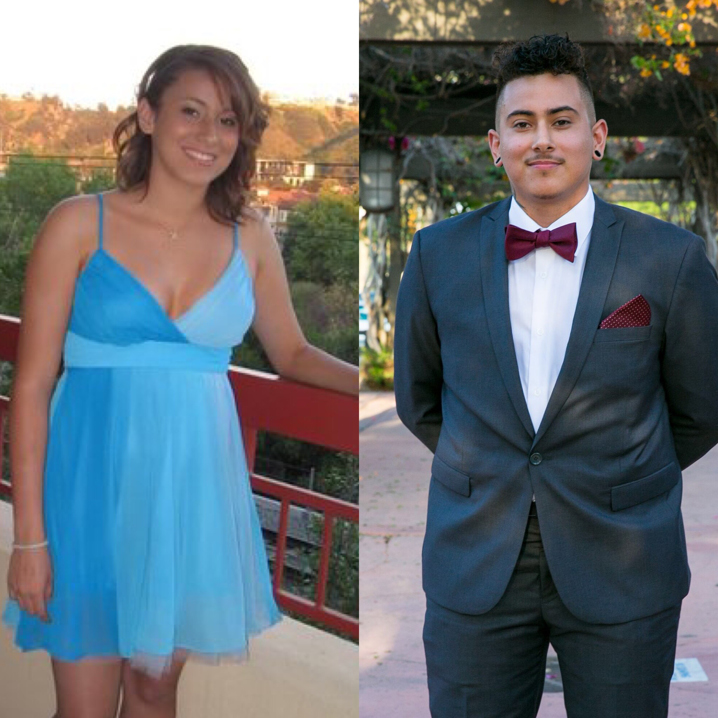

“My name is anthony, im 24, maybe 25 by the time you read this. On the left photo i am 15, on the right i am 24, on my wedding day to the love of my life. I never thought id live to be this old, its pretty mind blowing to me.”

READ THE STORY

“but when it’s come to lgbt issues, we are unable to married who we love, laws make us live apart from society.”

READ THE STORY

“I always hate to share my story because it brings back sad memories and makes me feel very down. I have faced a lot of violence, mob attacks, police cases because of my sexuality, rejection from landlords, family rejecting me as a terror.”

READ THE STORY

“I suffered a lot of bias at work because of my sexual orientation I have faced many challenges, and one of the worst challenges is access to health care services for being a trans woman.”

READ THE STORY

“He brought me to his house. I did not realize I was brought to his house because I was boozed off. I realized myself with two guys in the bed. Him and I, and the other one. And I was very much ashamed and so sad because someone I trust and I wanted to be with could do this thing to me.”

READ THE STORY

“we aren’t afraid to show the world our love, but sometimes it’s not that easy. we receive bad words or comments from people for no reason”

READ THE STORY

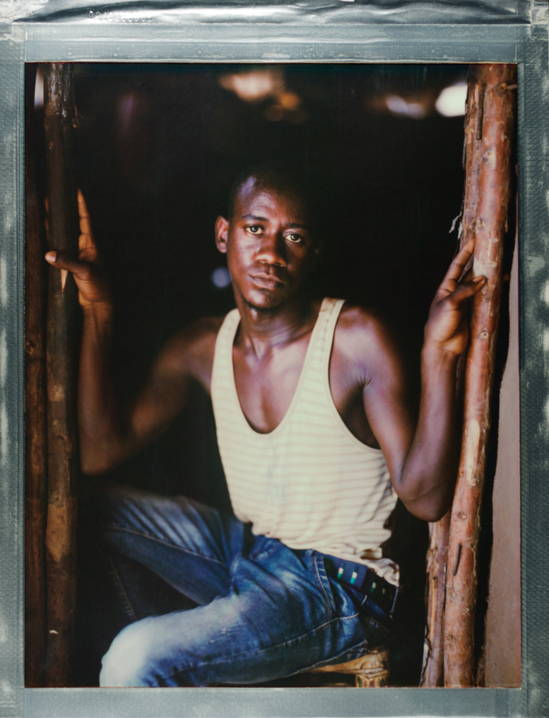

“It’s not easy in Ghana here. You say you are a gay. It’s not easy at all.”

READ THE STORY