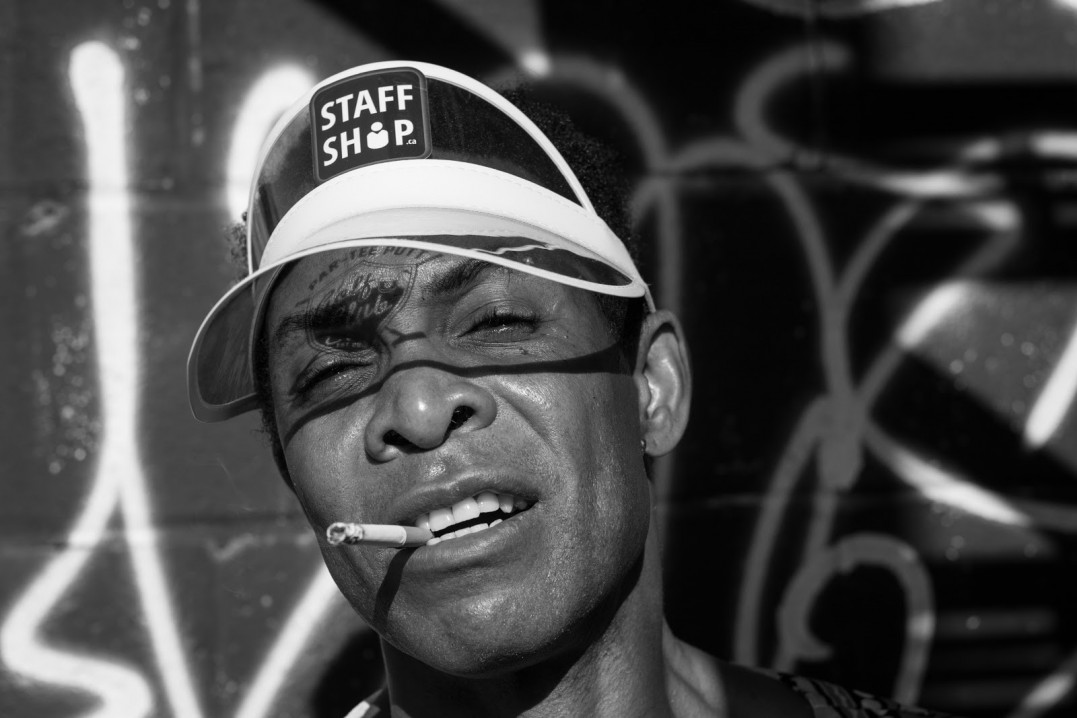

Rolyn Chambers / Canada

“THE JOURNEY OF ROLYN

Kicked out by my stepfather at 16 for being gay, I’ve been immersed in Toronto’s queer community since I set foot in my first lesbian dance club, the long since closed Chez Moi and my first gay club Komrads, also long since closed, on the same magical night many, many years ago. Born in Jamaica and raised in Toronto since five in predominantly white schools and predominantly white neighbourhoods in the 80s and 90s, I’ve had an odd journey. But this journey was prefaced with sound advice from my mother. She always told me to remember that people will only see the surface at first. When you leave the house, “you must look presentable and act accordingly because you are always being watched, always being judged.” By doing these two things I was able to hold my head high, not to appear better than anyone, but to ensure everyone knew I was not less than them. This enabled me, a black gay kid who preferred drawing to sports, to adapt into any circumstance and to connect with many different types of people. My journey led me as an adult to immerse myself primarily in what most would call the white gay circuit music scene. I’ve always felt more comfortable in scenes that not only played the type of music I liked but had a somewhat diverse mix of people who partied to it. When I graduated art school I began writing my Deep Dish column for Fab Magazine and Xtra Magazine. For 15 years I covered the queer entertainment scene going from mostly white circuit parties to mostly black (DJ Blackcat) hip hop parties, from fashion shows, art events, high society fundraisers and everything in between. Fab was often criticized for being too white and not showcasing enough queer people of colour. When I came onboard in 2001, under editor Mitchel Raphael, we tried to turn this perception around. My centre spread column in particular delved into the social scenes of every queer subsection in and around the city and I made sure that each of my columns was as varied and diverse as possible. It was also a time when, for various reasons, some black men were not comfortable having there photos published in a gay magazine. When I went to a more mixed queer event, black gays were always up for getting their photos taken. My photographer, Tony Fong, and I actually sought them out. However, when I went to a party attended mostly (sometimes only) by black gay men, those who looked like me, getting photos was like pulling teeth. It was depressing. What was ironic about my time at Fab was that even though people still saw the magazine as manly catering to white gay men, the one column (that came with society column style pictures of what went down every week) that so many people said they turned to first, was curated by a black man and photographed by a Chinese man. Tony and I went everywhere together and to many in the various scenes we inhabited, we were the face of the magazine. In this last year my journey has awakened something that had always been within. I had always refused to believe I was different in any way from the mostly white gay men that surrounded me at many of the events I went to. Though they never said it, I was different. I was not like them. The explosive racially charged events that have taken place, especially in 2020, have led me to debate online (and block) many in my quest to educate them (and to an extent myself) on intersectionality and the BLM movement. Many of these white men who followed me had been with me since I was a columnist with Fab and Xtra magazines. They now saw me as different as well. But even with this late knowledge I still follow my mother’s advice. Look presentable and act accordingly. I know I’m being watched and I’m being judged. My head is still held high and this has allowed me to still appreciate every aspect of our varied queer community.”