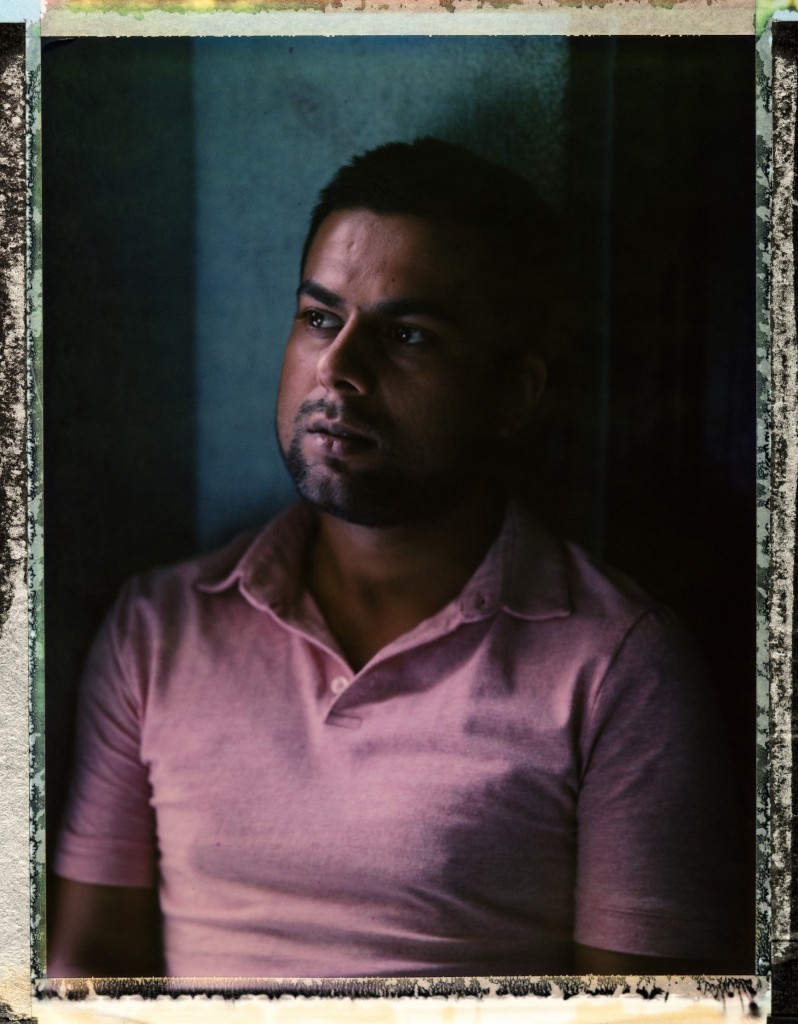

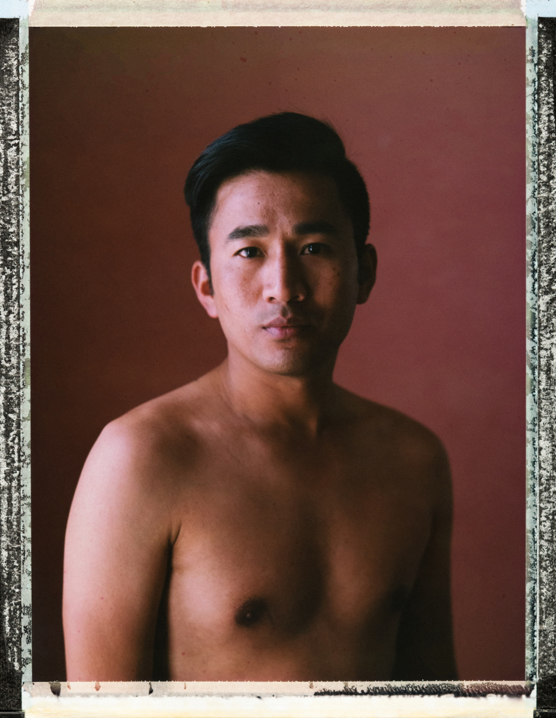

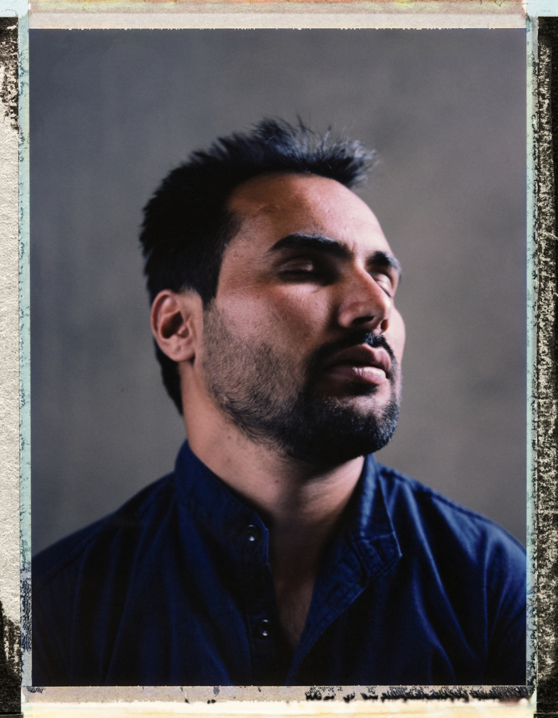

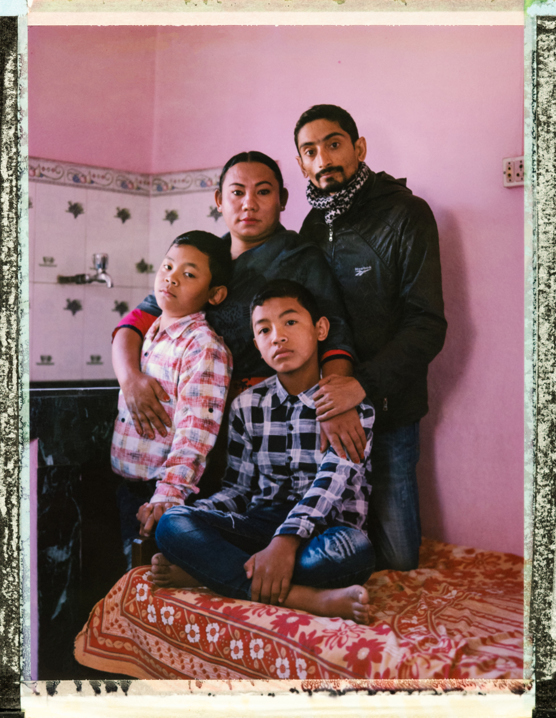

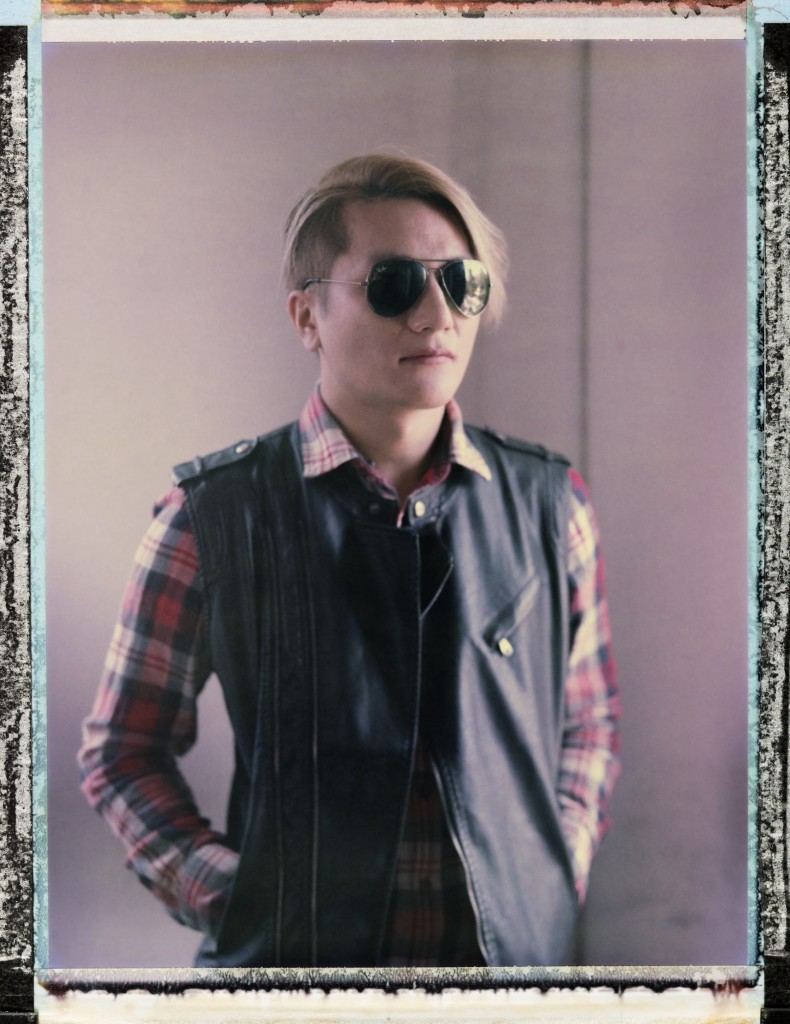

Anuj Peter/

Nepal

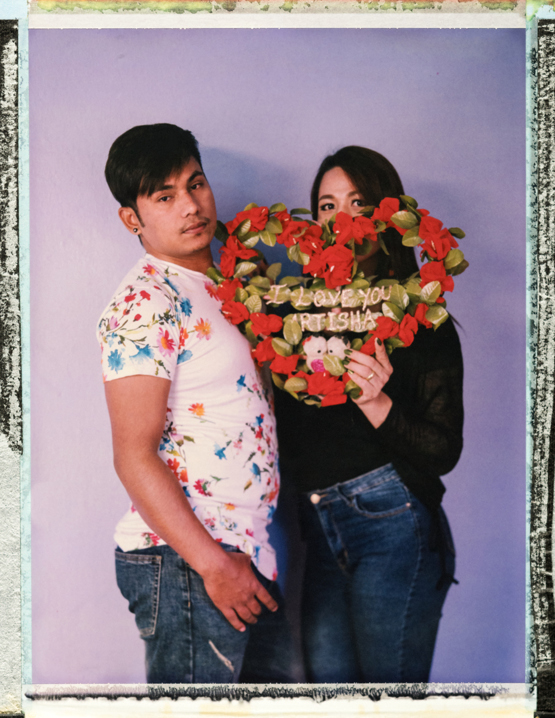

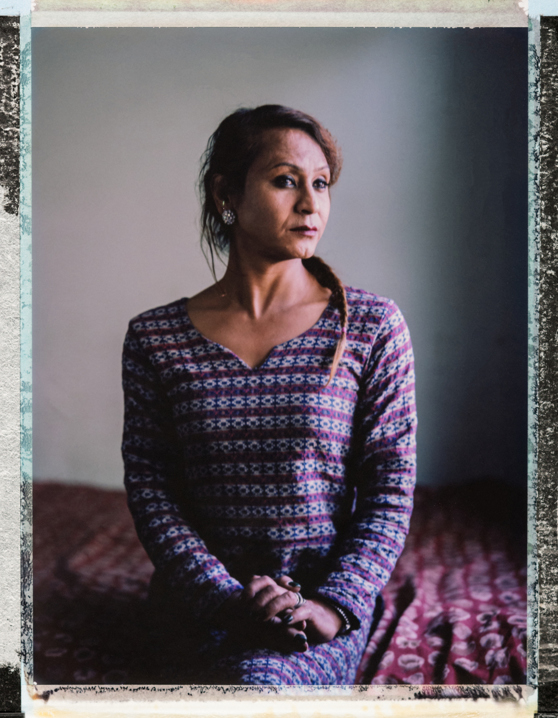

“When it comes to reality it was really different. At that time I scared that marriage is not only about the sum of being husband and wife to society. Another part is physical and emotional attachment as well. So I think to quit that relationship.“

READ THE STORY